Your S&P 500 Index Fund Costs More Than You Think

Here’s an investment opportunity for your consideration. It’s managed by an investment committee that seeks to build a portfolio to be representative of the U.S. economy. The committee meets regularly to determine what stocks to add to or remove from the portfolio, and routinely makes between 10-40 changes per year. These decisions are not made according to a set schedule, nor does rebalancing occur on a regular basis—only when the committee determines changes and rebalancing are necessary. It’s touted as a “passively managed” equity portfolio, but because the stocks are selected by a group of expert investment analysts — human beings, in other words — calling it a passive portfolio seems to be a stretch.

Fortunately, it’s not a real mutual fund we’re talking about — it’s the S&P 500 Index.

In the words of David Blitzer, chairman of the S&P 500 Index committee, “There are no rigid or absolute rules for the S&P 500; the Index Committee have some discretion in selecting stocks or responding to market events.”

How is this process any different from what happens inside every actively managed mutual fund? It’s not. So why is an index fund targeting the S&P 500 deemed a passively-managed investment vehicle?

The financial factory has brainwashed the average investor into thinking indexing should be the backbone of an investment plan. The evidence of this brainwashing can be seen in the amount of money following this poorly designed index. Indexing to the S&P 500 is hurting investors. Here’s why:

Tracking turns investment managers into sheep

The investment managers behind the index funds that track the S&P 500 are not judged by investment performance. They are judged by how closely their results track the S&P 500. When it doesn’t, it’s called tracking error. Deviate from the index performance and you lose your job.

A target index like the S&P 500 is hardly managed in a passive way. As we mentioned, there is a committee of people who set the rules for including or removing a stock from the index. When a stock is added to the S&P 500, all index funds that track it also add the stock to their portfolio. And because all index additions are announced in advance – on average, four days before inclusion – there’s ample opportunity for the price to change, mostly to the advantage of savvy traders and the detriment of index fund investors.

Here’s a great example of this phenomenon at work from earlier this year, as cited in a Bloomberg article:

“Take American Airlines Group Inc., which joined the S&P 500 after markets closed on March 20. Because the addition of the carrier was announced four days earlier, nimble traders had plenty of time to get in front of the less fleet-footed. American jumped 11 percent over the span.

The cost was ultimately borne by index funds, which sparked an $8 billion buying frenzy in the two minutes right before the close — an amount equal to more than two weeks of the stock’s typical volume, data compiled by Bloomberg show.”

The index funds tracking the S&P 500 paid an 11% premium for American Airlines stock, only because it carried the Standard and Poor’s “seal of approval”. This is the massive hidden cost of index investing, and index fund investors are the ones paying the price. Other fund managers don’t announce their trades in advance. No other smart investor would either.

The “index premium” is real

Financial academics call the cumulative effect of these price movements the “index premium”. Dr. Antti Petajisto, portfolio manager at Blackrock, researched the index premium effect while at the NYU Stern School of Business. In his 2011 paper “The Index Premium and Its Hidden Cost for Index Funds”, he quantified the price changes for both the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 indexes between the announcements of index changes and the effective dates.

“For additions to the S&P 500 and Russell 2000, we find that the price impact from announcement to effective day has averaged +8.8% and +4.7%, respectively, and −15.1% and −4.6% for deletions.”

The “index effect” works on both sides of the trade. Adding a stock to the S&P 500 will inflate its price because of the tremendous amount of buying pressure from index mutual funds. Likewise, removing a stock from the S&P 500 Index will deflate its price because all of the index funds now have to sell their shares. The funds end up selling at lower prices, which ultimately affects the returns index fund investors achieve.

Market weighting tips the scales

The next challenge – big stocks determine the outcome. The S&P 500 is a “capitalization weighted” index. That means larger companies – defined by market capitalization, or the number of outstanding shares multiplied by the current share price – have a greater representation in the index. So Apple, being the largest U.S. company with a “market cap” of $649 billion (as of August 31, 2015) receives a heavier weighting in the index than Joy Global, whose $2.3 billion market cap makes it the smallest stock in the S&P 500 (as of August 31, 2015.)

So when Apple’s stock does well, it has a bigger influence on the S&P 500’s performance than when Joy Global’s stock does well. Of course, that works on the downside too.

The bigger stocks overwhelm the smaller stocks and make the S&P 500 top-heavy. At the end of 2014, the top 10 stocks represented about 18% of the index. The top 25 stocks were 32% of the total. The top 50 stocks were a whopping 46.5% of the index.

Think about that – 10% of the stocks in the S&P 500 accounted for almost half of its market value. You may think you’re diversified in an S&P 500 index fund, but really you are not.

Moreover, these “mega-cap” stocks have an obvious impact on the index’s performance. According to LJPR Financial Advisors, the top 36 S&P 500 stocks contributed over 55 percent of the index’s total return for 2014. But the effect also works in reverse – when any of these stocks decline, they’re more likely to drag the S&P 500 Index down too.

Diversification is supposed to help tame the risk of over-weighting to a few stocks or sectors. But investors should ask how diversified is an S&P 500 index fund when performance depends on just a handful of stocks.

When the benchmark ceases to be a benchmark

The FDA requires drug companies to have a control group when testing new drugs. The concept is simple – you need a group of people taking the drug and a group of people not taking the drug (the control group) to determine how helpful or harmful the drug was.

Market indexes were created to be the control group for your investment portfolio, so you can measure the performance your investment performance against a representative average. The popular market indexes were created decades ago – the modern incarnation of the S&P 500 Index began in the 1950s, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average has an even longer history back to the 1890s. But once the indexes began being used as benchmarks for money managers, the financial industry soon learned that the majority of fund managers routinely failed to improve upon the performance of these control groups (a trend that remains in place even today).

Index funds were introduced in the 1970s to counter this trend, proclaiming in a way that “if you can’t beat them, join them.” Burton Malkiel spawned the index fund idea in his influential book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street, wishing for a low-cost, low-turnover portfolio that would avoid the under-performance common among active mutual fund managers. “Whenever below-average performance on the part of any mutual fund is noticed,” he wrote, “fund spokesmen are quick to point out ‘You can’t buy the averages.’ It’s time the public could.”

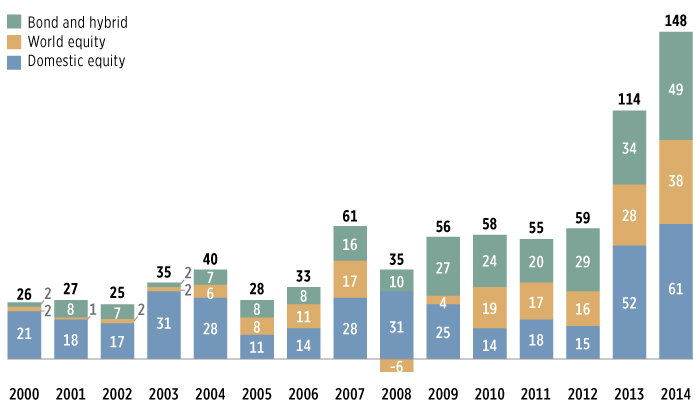

The index funds for individual investors came to market in the early 1980s with the launch of the Vanguard flagship S&P 500 Index Fund. Since that time, index funds as an asset class have exploded in popularity, attracting $148 billion in new money in 2014 according to the Investment Company Institute. That’s over 5 times the amount of money that investors placed in index funds in 2000.

At the end of 2014, index funds accounted for over $2.1 trillion of net assets in the market. And four of every five of those dollars were allocated to S&P 500 index funds. With so much money now tracking this one index, the problems will become meaningful for investors. But without a control group, it is very difficult to ascertain exactly how much these costs are impacting the long-term investment performance of index fund investors.

The good news is you can still enjoy the benefits of a passive portfolio, keep your costs low and completely avoid the problems of indexing. There are a few simple changes to help you achieve a better outcome with your portfolio. Look for those in my next blog.